Please wait a few moments while we process your request

Jim Campbell

Explorations of Meaning in Quantized Information

With the grant received from the Daniel Langlois Foundation in 2000, Jim Campbell endeavoured to explore visual and poetic meaning in the small amounts of digital information that make up conventional digital representation. Assuming that meaning can be expressed with very little information, Campbell began experimenting with how the human mind can process representation. He created a series of works that differ according to the number of pixels used. An experiment in digital abstraction, the Ambiguous Icons series pursues the notion that information and meaning are exponentially different. The low resolution of the works incites the viewer to search colour, form and movement for meaning, and to construct and imagine the context rather than receive it passively.

The technical basis for these works is Jim Campbell's custom electronics. In this particular series, his technology was inspired by a theory developed by the engineer Harry Nyquist (1889-1976), to whom one of the works in the series is dedicated. (1) Nyquist worked at Bell Labs where in 1928 he published the article "Certain Topics in Telegraph Transmission." (2)

Work on digital transmission began back in the 1920s, when Bell System researcher Harry Nyquist determined that it was possible to encode an analog signal in digital form if the analog signal was sampled at twice its frequency. Since it was determined at that time that an adequate analog voice signal could be transmitted at 4,000 Hz, such a signal would have to be sampled 8,000 times a second (2 x 4,000), according to Nyquist. Each sample could then be encoded and transmitted, and there would be enough information in the encoded signal for the original voice signal to be reconstructed into an understandable analog signal at the receiving end. (3)

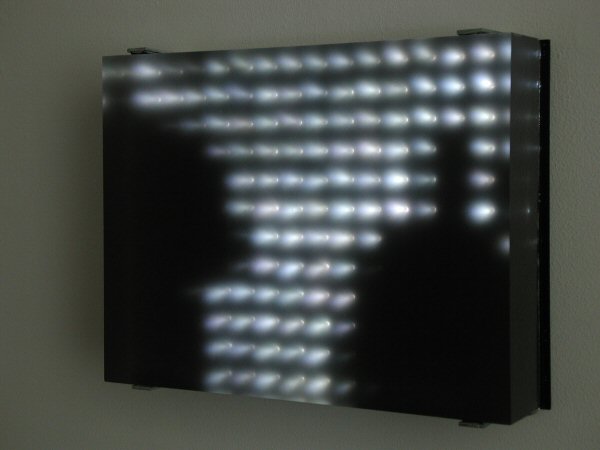

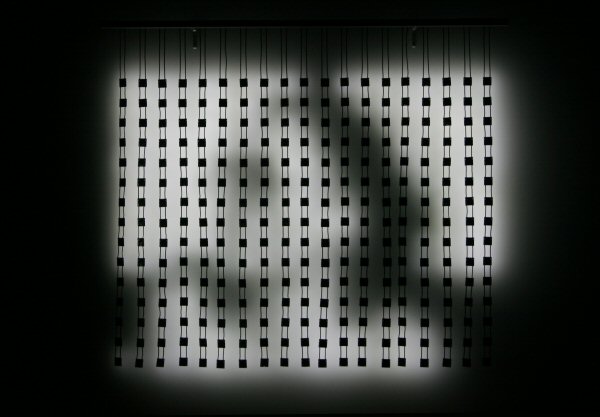

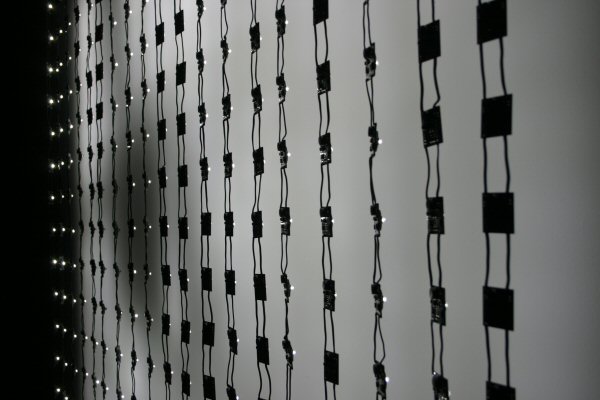

In this series, Campbell addresses the idea of a filter in Nyquist's process of transforming analog into digital and vice versa. In his works, Campbell uses an actual filter or Plexiglas screen that makes it less likely that the viewer will see the actual pixels. Therefore, although Campbell has substantially reduced the resolution of the image to the point of abstraction, he has filtered the resulting pixelation and has thus rendered the digital image analog, in an almost figurative sense. In Portrait of a Portrait of Harry Nyquist (2000) and Portrait of a Portrait of Claude Shannon (2000), Campbell places Plexiglas screens in front of grids of LEDs displaying photos of each man taken from their obituaries. The pixels are masked, and fuzzy images of the men emerge. Campbell notes that:

"though these works seem "out of focus," I would argue that it is not the image that is made out of focus by the screen but that it is the pixels or artifacts of the information that are defocused by the screen. This is demonstrated on the videotape, where the image is seen more "clearly" and the pixels less "clearly" when the diffusing screen is placed in front of the image." (4)

As well, throughout the research and development process, Campbell came to realize that the nature of the pixels made a huge difference on the viewer's resulting relationship with the artwork. He found that by using three-colour pixels, rather than black and white, he could reduce the number of pixels while still maintaining an identifiable image. As noted by Campbell, Ambiguous Icon #2 Fight (2000) is the perfect example of this pixel play. In this piece, footage from a boxing match is used at a very low resolution. If Campbell had kept the pixels in black and white, it would have been very difficult to make out the human form of the boxers as they move in the piece. However, when 88 x 3 colour pixels are used, the human body emerges from the digital image as flesh tones delineate form and the red of the boxing gloves engender meaning and situate the spectator.

"Instead of trying to make technology invisible ... Campbell looks to the liminal point between clarity and confusion-that point of 'flicker fusion' where our eyes grab legible images out of pure static." (5) At a time when technology thrives on simulation and replication, Campbell attempts to introduce the opposite and offer reassurance that meaning can be captured and understood without surfeit.

Work on digital transmission began back in the 1920s, when Bell System researcher Harry Nyquist determined that it was possible to encode an analog signal in digital form if the analog signal was sampled at twice its frequency. Since it was determined at that time that an adequate analog voice signal could be transmitted at 4,000 Hz, such a signal would have to be sampled 8,000 times a second (2 x 4,000), according to Nyquist. Each sample could then be encoded and transmitted, and there would be enough information in the encoded signal for the original voice signal to be reconstructed into an understandable analog signal at the receiving end. (3)

In this series, Campbell addresses the idea of a filter in Nyquist's process of transforming analog into digital and vice versa. In his works, Campbell uses an actual filter or Plexiglas screen that makes it less likely that the viewer will see the actual pixels. Therefore, although Campbell has substantially reduced the resolution of the image to the point of abstraction, he has filtered the resulting pixelation and has thus rendered the digital image analog, in an almost figurative sense. In Portrait of a Portrait of Harry Nyquist (2000) and Portrait of a Portrait of Claude Shannon (2000), Campbell places Plexiglas screens in front of grids of LEDs displaying photos of each man taken from their obituaries. The pixels are masked, and fuzzy images of the men emerge. Campbell notes that:

"though these works seem "out of focus," I would argue that it is not the image that is made out of focus by the screen but that it is the pixels or artifacts of the information that are defocused by the screen. This is demonstrated on the videotape, where the image is seen more "clearly" and the pixels less "clearly" when the diffusing screen is placed in front of the image." (4)

As well, throughout the research and development process, Campbell came to realize that the nature of the pixels made a huge difference on the viewer's resulting relationship with the artwork. He found that by using three-colour pixels, rather than black and white, he could reduce the number of pixels while still maintaining an identifiable image. As noted by Campbell, Ambiguous Icon #2 Fight (2000) is the perfect example of this pixel play. In this piece, footage from a boxing match is used at a very low resolution. If Campbell had kept the pixels in black and white, it would have been very difficult to make out the human form of the boxers as they move in the piece. However, when 88 x 3 colour pixels are used, the human body emerges from the digital image as flesh tones delineate form and the red of the boxing gloves engender meaning and situate the spectator.

"Instead of trying to make technology invisible ... Campbell looks to the liminal point between clarity and confusion-that point of 'flicker fusion' where our eyes grab legible images out of pure static." (5) At a time when technology thrives on simulation and replication, Campbell attempts to introduce the opposite and offer reassurance that meaning can be captured and understood without surfeit.

Angela Plohman © 2002 FDL

(1) See Jim Campbell's work Portrait of a Portrait of Harry Nyquist (2000).

(2) Harry Nyquist, "Certain Topics in Telegraph Transmission", AIEE, Vol. 47 (1928): 214-216.

(3) "Developing a Digital Signal," Bell Labs Technology

(4) This citation is taken from Jim Campbell's final report submitted to the Daniel Langlois Foundation, August 2001.

(5) Alex Galloway, "Conversions," Rhizome.org .

Related pages:

Jim Campbell

Jim CampbellOriginally a filmmaker, Campbell turned to science after having worked for several years on a personally difficult film on mental illness.

Jim Campbell, Representing Simultaneous Images

Jim Campbell, Representing Simultaneous ImagesKeying is a technique for overlaying several video sources onto the same image.

External link:

Jim Campbell:

http://www.jimcampbell.tv/

http://www.jimcampbell.tv/