Please wait a few moments while we process your request

Catherine Richards

(Ottawa, Ontario, Canada)

Catherine Richards lives and works in Ottawa, Canada, where she is an assistant professor in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Ottawa. She received a bachelor's degree in English literature from York University in 1971 and a bachelor's degree in visual arts from the University of Ottawa in 1980.

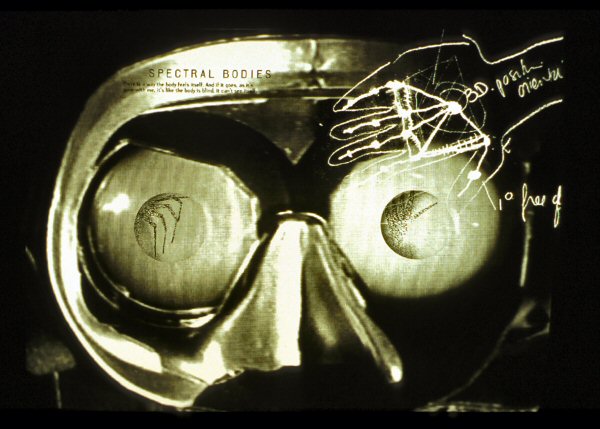

In 1991, Richards and Nell Tenhaaf organized the Virtual Seminar on the Bioapparatus, (1) conference at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Alberta. This was one of the first public arts events in Canada to examine virtual realities and the interfaces between technology and the human body. This innovative project earned her the 1992 Corel Prize from the Canadian Conference of the Arts. In 1993, she won the Petro-Canada Award in Media Arts from the Canada Council for the Arts for her outstanding use of new technologies in media arts and, specifically, for Spectral Bodies (1991). That same year, her interactive work Virtual Body was shown at the Antwerp '93 Festival in Belgium.

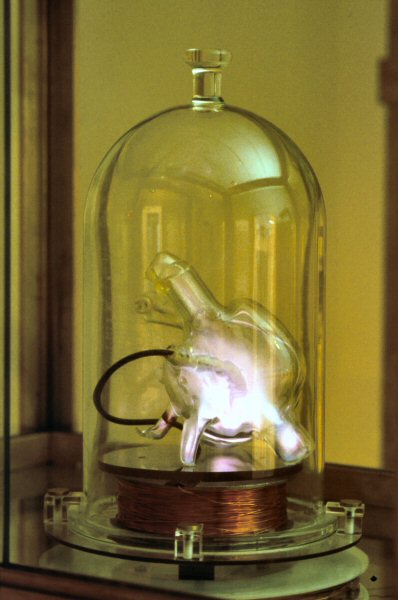

She received a Canadian Centre for the Visual Arts Fellowship at the National Gallery of Canada for 1993 and 1994 to continue her work in contemporary art. For 1994 and 1995, the gallery awarded her the Claudia De Hueck Fellowship in Art and Science for her Charged Hearts project (1997). Also in 1995, her Curiosity Cabinet at the End of the Millennium was commissioned for the exhibition Self Determination/Body Politic at the Gemeentenmuseum in Arnhem, the Netherlands. What's distinctive about Richards's work, especially in Charged Hearts, is how she gathers wide-ranging technological and scientific resources and forms multidisciplinary teams of computer scientists, physicists, technologists and craftsmen who all play a part in producing the work.

Richards has always referred explicitly to the computerized environments she explores (smart Environments, the smart House). In her work, humans interact cybernetically with their surroundings via countless sensory interfaces. Her work questions the idea of the autonomous subject within computerized environments. Richards stresses the desires and pleasures that readily prompt us to relinquish our autonomy:

"But a network is a two-way street. Being part of the system, logging in, means vulnerability, and the more subtle the system desired, the more intimate that relation. As our intimacy grows, so does our vulnerability. Within such pleasurable surveillance we wish to be both agent and object, spider and fly." (2)

In a number of her works, including Charged Hearts, the artist sets out to reveal this burgeoning of "pleasurable surveillance" environments that assign us to the role of servo-mechanism. (3)

Richards notes that in the discussion on new technological environments, the subject is often considered autonomous. Marvin Minsky (Toshiba professor of media arts and sciences and professor of electrical and computer engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and other writers even make a case for greater autonomy by the subject and a consolidation of the faculties and powers of a unitary subject in the new computerized environments. Richards writes :

"If the brain is a computer and the spine is a coaxial cable, as scientists such as Marvin Minsky have suggested, then it extends the image of the nervous system as an information network. Thus, shedding the 19th-century perspective of the body as a self-contained organism, the body cannot now, in a sense, be distinguished from the information it requires to function. As such, it is illogical to keep it unplugged from its environment-keeping it in the dark, as it were." (4)

Richards's works draw attention to an illusion cultivated by subjects that attempt to maintain their integrity in technological environments. This is the debate that surrounds her work, this area of ambivalence regarding the new technological environments in which tensions are played out between the subject's alienation and loss of autonomy and the values of liberty and control associated with technologies.

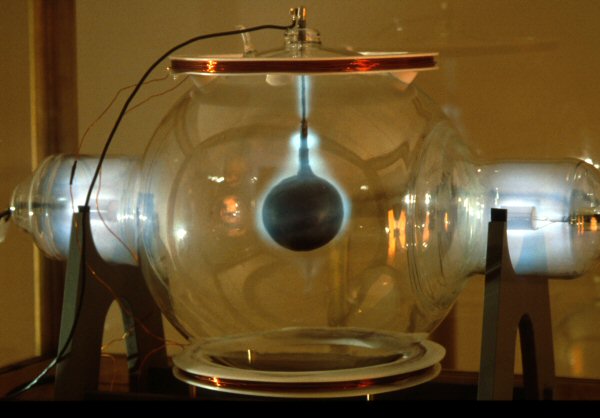

Curiosity Cabinet at the End of the Millennium and Virtual Body just like Charged Hearts, are inspired by "primitive" technologies. Curiosity Cabinet centres on early electrical and electromagnetic technologies, specifically the Faraday cage, a kind of chamber shielded from the ambient magnetic waves and used here to disconnect viewers who shut themselves in it. Virtual Body takes the form of a wood-panelled box, a combination curiosity cabinet and 19th-century optical instrument. Despite their differing degrees of technological and conceptual complexity, these two works focus on the body and its relationship with its environment, whether electromagnetic or spatial. The viewers become a point of reference, like a disconnected curiosity from the cabinet or a pole attracting the eye and creating order in the multiple vanishing points in the rococo room, with its pictures and mirrors.

"If the male human is the only human, the female cyborg is the only cyborg." (5)

When we plug in to networks, give up part of our autonomy to computer systems and subject ourselves to cybernetic "pleasures," don't we become cyborgs? Richards has written about this and questioned the parallel that some have drawn, perhaps too quickly, between digital technologies and the feminist project to redefine feminine subjectivity. How paradoxical it is that technologies most often designed by the military to gain greater mastery and control may promote so-called feminine characteristics: a subjectivity inclined to be dispersed in a web of connections, accustomed to operating in a network of interconnections and interlocutions, a subjectivity on the uncertain, indefinite edge and in a constant intersubjective relation with others. To Richards, this is a bad joke that works only through a certain nostalgia. In fact, no one can predict what will become of human subjectivity, male or female, in the emerging computerized world. Should we infer that the male imagination once again dominates telematic constructions in a kind of desire for self-generation that obliterates the other, and that works created with these technologies are a new form of bachelor machines? This is yet another debate sparked by Richards's work.

In 1991, Richards and Nell Tenhaaf organized the Virtual Seminar on the Bioapparatus, (1) conference at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Alberta. This was one of the first public arts events in Canada to examine virtual realities and the interfaces between technology and the human body. This innovative project earned her the 1992 Corel Prize from the Canadian Conference of the Arts. In 1993, she won the Petro-Canada Award in Media Arts from the Canada Council for the Arts for her outstanding use of new technologies in media arts and, specifically, for Spectral Bodies (1991). That same year, her interactive work Virtual Body was shown at the Antwerp '93 Festival in Belgium.

Richards has always referred explicitly to the computerized environments she explores (smart Environments, the smart House). In her work, humans interact cybernetically with their surroundings via countless sensory interfaces. Her work questions the idea of the autonomous subject within computerized environments. Richards stresses the desires and pleasures that readily prompt us to relinquish our autonomy:

"But a network is a two-way street. Being part of the system, logging in, means vulnerability, and the more subtle the system desired, the more intimate that relation. As our intimacy grows, so does our vulnerability. Within such pleasurable surveillance we wish to be both agent and object, spider and fly." (2)

In a number of her works, including Charged Hearts, the artist sets out to reveal this burgeoning of "pleasurable surveillance" environments that assign us to the role of servo-mechanism. (3)

Richards notes that in the discussion on new technological environments, the subject is often considered autonomous. Marvin Minsky (Toshiba professor of media arts and sciences and professor of electrical and computer engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and other writers even make a case for greater autonomy by the subject and a consolidation of the faculties and powers of a unitary subject in the new computerized environments. Richards writes :

"If the brain is a computer and the spine is a coaxial cable, as scientists such as Marvin Minsky have suggested, then it extends the image of the nervous system as an information network. Thus, shedding the 19th-century perspective of the body as a self-contained organism, the body cannot now, in a sense, be distinguished from the information it requires to function. As such, it is illogical to keep it unplugged from its environment-keeping it in the dark, as it were." (4)

Richards's works draw attention to an illusion cultivated by subjects that attempt to maintain their integrity in technological environments. This is the debate that surrounds her work, this area of ambivalence regarding the new technological environments in which tensions are played out between the subject's alienation and loss of autonomy and the values of liberty and control associated with technologies.

Curiosity Cabinet at the End of the Millennium and Virtual Body just like Charged Hearts, are inspired by "primitive" technologies. Curiosity Cabinet centres on early electrical and electromagnetic technologies, specifically the Faraday cage, a kind of chamber shielded from the ambient magnetic waves and used here to disconnect viewers who shut themselves in it. Virtual Body takes the form of a wood-panelled box, a combination curiosity cabinet and 19th-century optical instrument. Despite their differing degrees of technological and conceptual complexity, these two works focus on the body and its relationship with its environment, whether electromagnetic or spatial. The viewers become a point of reference, like a disconnected curiosity from the cabinet or a pole attracting the eye and creating order in the multiple vanishing points in the rococo room, with its pictures and mirrors.

"If the male human is the only human, the female cyborg is the only cyborg." (5)

When we plug in to networks, give up part of our autonomy to computer systems and subject ourselves to cybernetic "pleasures," don't we become cyborgs? Richards has written about this and questioned the parallel that some have drawn, perhaps too quickly, between digital technologies and the feminist project to redefine feminine subjectivity. How paradoxical it is that technologies most often designed by the military to gain greater mastery and control may promote so-called feminine characteristics: a subjectivity inclined to be dispersed in a web of connections, accustomed to operating in a network of interconnections and interlocutions, a subjectivity on the uncertain, indefinite edge and in a constant intersubjective relation with others. To Richards, this is a bad joke that works only through a certain nostalgia. In fact, no one can predict what will become of human subjectivity, male or female, in the emerging computerized world. Should we infer that the male imagination once again dominates telematic constructions in a kind of desire for self-generation that obliterates the other, and that works created with these technologies are a new form of bachelor machines? This is yet another debate sparked by Richards's work.

Jean Gagnon © 2002 FDL

(1) Catherine Richards and Nell Tenhaaf, eds., Virtual Seminar on the Bioapparatus, Banff: The Banff Centre for the Arts, 1991.

(2) Artist's statement, unpublished, National Gallery of Canada project files, Ottawa, September 1996, n.p.

(3) Marshall McLuhan refers often to this notion in Understanding Media (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

(4) Catherine Richards, "Virtual bodies: what a blow that phantom gave me," in Angles of incidence, video reflections of multimedia artworks, curated by Sara Diamond (Banff: The Banff Centre for the Arts, 1993), p. 18.

(5) Sadie Plant, quoted in "Fungal intimacy: the cyborg in feminism and media art," Clicking in: hot links to a digital culture, Lynn Hershman Leeson, ed. (Seattle: Bay Press, 1996).

Related pages:

Catherine Richards, Three New Artworks

Catherine Richards, Three New ArtworksCatherine Richards continues exploring the pressures, changes and contradictions that drive our understanding of ourselves.

Caroline Langill, Shifting Polarities, Interview with Catherine Richards

Caroline Langill, Shifting Polarities, Interview with Catherine RichardsCatherine Richards considers herself an artist working in old and new media.

External link:

Catherine Richards:

http://www.catherinerichards.ca/

http://www.catherinerichards.ca/