Please wait a few moments while we process your request

Caroline Langill, Shifting Polarities

Early electronic media works

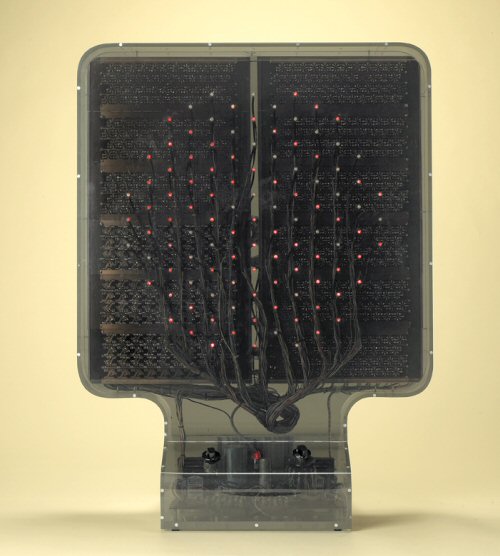

First Tighten Up on the Drums (1968) was Norman White’s first electronic media work incorporating several hundred early-vintage digital-integrated circuits, which had been donated to the artist by the Sprague Electric Company. The object of the work was its autonomous generation of light patterns, but in retrospect White sees it as an early experiment in cellular automata, introducing the possibility of producing self-sustaining artworks that evolve and learn. (1) It was produced specifically for the E.A.T. group exhibition Some More Beginnings at the Brooklyn Museum, and White recalls taking it to New York in its own seat on the airplane, much to the amusement of the flight attendants. First Tighten Up on the Drums, an autonomous work with its own mechanical “brain,” was not the first robotic work purchased by the National Galley of Canada (NGC). De La, produced by Michael Snow between 1969 and 1971, in collaboration with engineer Pierre Abeloos, was acquired by the NGC in 1972. De La set a new precedent as work that was robotic, interactive and responsive to its environment.

Hybrid performance work was highly influential for artists working in new media art. Victoria-based Mowry Baden produced his work Seat Belt in 1971. With no electronics, the work is not an electronic media work, but it is a precedent in many ways for systems-based interactive art practices. With its apparatus derived from the automobile, it refers to technology in its absence. Also, the audience member/participant/interactor must engage with the work by tying into the belt, in order to even “see” it. It was the task-oriented nature of the work that drew Jack Burnham to it, and for this reason, Seat Belt should be acknowledged for its prescient nature. Purchased by the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1971, the work bridges the space between traditional sculpture and interactive media.

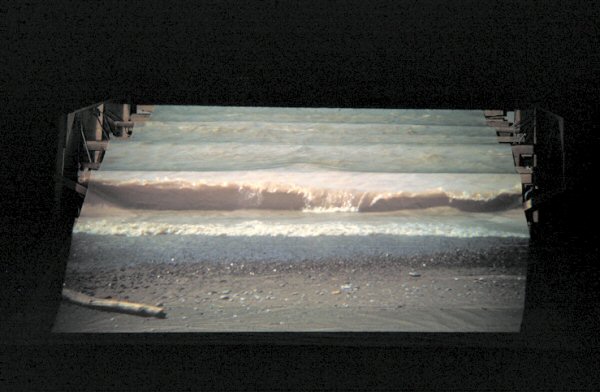

Murray Favro’s Synthetic Lake, produced between 1972 and 1973, was featured in the exhibition Another Dimension and acquired by the National Gallery of Canada in 1974. Much like Baden, Favro has largely been considered a sculptor, and in fact Synthetic Lake consists of no electronics other than an electric motor. The work’s mechanical emulation of the movement of a lake, coupled with the film of the lakeshore with its pulsating waves projected onto the canvas cover of the machine, is an uncanny integration of art and engineering. Provoking disorientation in the viewer, this work expanded notions of cinema and foreshadowed the potential of immersive technologies to change our dimensional relationship to film.

The Faraday cage has recently emerged as a primary metaphor in discussions of our relationship to technology. Tom Sherman’s Faraday Cage of 1973 was formally and conceptually utilitarian, addressing the encroachment of electro-magnetic radiation into our day-to-day lives. Catherine Richards’ Curiosity Cabinet at the End of the Millenium (1995) emerges out of a feminist critique of technology 22 years later. Both are worthy of consideration as significant works in the history of electronic media. Like Seat Belt, neither includes electronics, but they are nevertheless embedded and active within contemporary discourses on technology.

Murray Favro’s Synthetic Lake, produced between 1972 and 1973, was featured in the exhibition Another Dimension and acquired by the National Gallery of Canada in 1974. Much like Baden, Favro has largely been considered a sculptor, and in fact Synthetic Lake consists of no electronics other than an electric motor. The work’s mechanical emulation of the movement of a lake, coupled with the film of the lakeshore with its pulsating waves projected onto the canvas cover of the machine, is an uncanny integration of art and engineering. Provoking disorientation in the viewer, this work expanded notions of cinema and foreshadowed the potential of immersive technologies to change our dimensional relationship to film.

The Faraday cage has recently emerged as a primary metaphor in discussions of our relationship to technology. Tom Sherman’s Faraday Cage of 1973 was formally and conceptually utilitarian, addressing the encroachment of electro-magnetic radiation into our day-to-day lives. Catherine Richards’ Curiosity Cabinet at the End of the Millenium (1995) emerges out of a feminist critique of technology 22 years later. Both are worthy of consideration as significant works in the history of electronic media. Like Seat Belt, neither includes electronics, but they are nevertheless embedded and active within contemporary discourses on technology.

Caroline Langill © 2009 FDL

(1) Norman White, “Norm the Artist, Oughtist, and Ne’er-do-well” (accessed May 23, 2008):

http://www.normill.ca/artpage.html

Index:

- Caroline Langill, Shifting Polarities

• Introduction

• Early electronic media works

• Electronic media in 1974

• Between science and art

• Machinic aesthetics

• Interaction and immersion

• Conclusion

• Bibliography

• Selected works - Artist bios and interviews

• Doug Back

• Mowry Baden

• Jean-Pierre Boyer

• Roland Brener

• Diana Burgoyne

• Max Dean

• Alan Dunning

• Murray Favro

• Vera Frenkel

• Juan Geuer

• Laura Kikauka

• Gordon Monahan

• Nancy Paterson

• Catherine Richards

• David Rokeby

• Michael Snow

• Tom Sherman

• Jana Sterbak

• Nell Tenhaaf

• Norman White