Please wait a few moments while we process your request

Frances Dyson, And then it was now

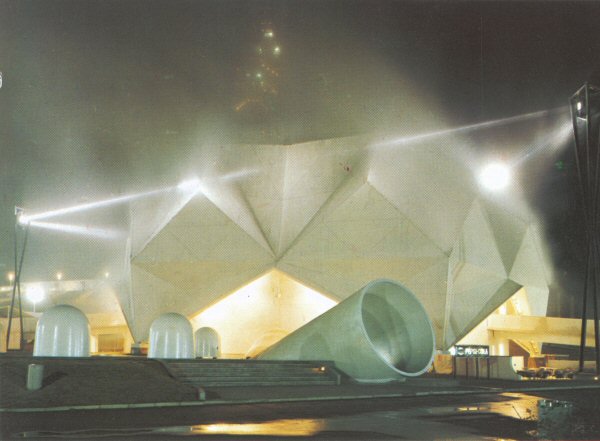

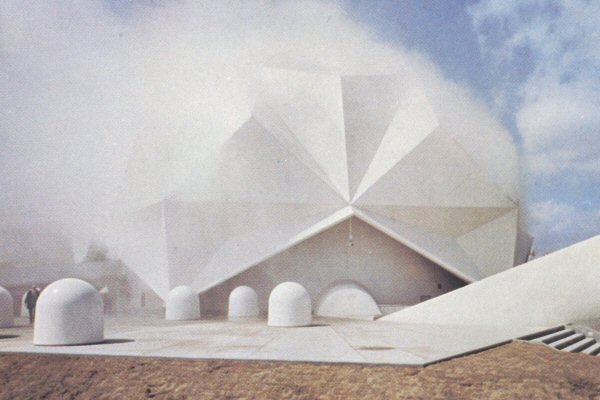

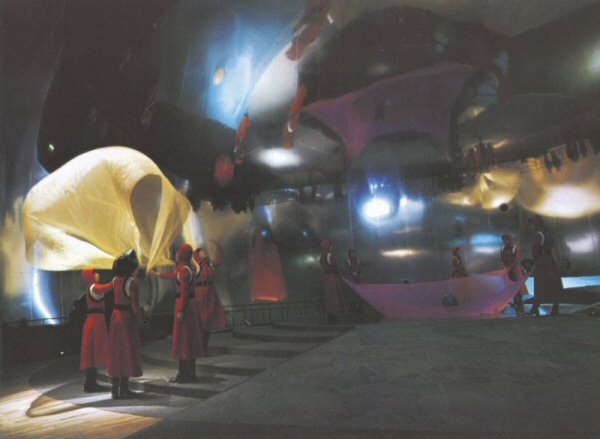

The Pavilion

Why the Pavilion?

Relationships between artists and engineers evolved significantly with the Pavilion. Whereas, in 9 Evenings, artists related primarily to engineers, with the Pavilion project their main concern was with corporate rather than engineering culture. This shift is perhaps best introduced in Klüver’s press statement, entitled “Background,” which was released jointly by E.A.T. and Pepsi-Cola on September 30, 1969. It begins as follows: “E.A.T. is interested in Pepsi-Cola, not art. Our organization tried to interest, seduce and involve industry into participating in the process of making art.” (1)

According to Calvin Tomkins, E.A.T. became involved in the Osaka Pavilion Project through Klüver, who had been contacted by Robert Breer. Breer, the first artist to become involved, heard about the project from David Thomas, Vice President for Marketing and Distribution with Pepsi-Cola International. Prior to his involvement in 9 Evenings, Breer had been ‘leery’ of the artist-engineer collaboration, although he found the open-ended approach employed by Klüver exciting. When Breer suggested to David Thomas that the Pepsi Company bring in E.A.T. to coordinate the project, it was because he felt that, through E.A.T., artists could cope with the commercial establishment without getting broken. E.A.T. could act as a buffer behind which they could operate more freely and more effectively in their own style. Robert Whitman, who was drawn into the Pepsi project, shared Breer's conviction. “With E.A.T.,” he said, “artists have for the first time had access to professionals on their own level in other worlds. This is a funny thing. Any artist, whether or not he had anything to do wit E.A.T., has professional status and is suddenly more respectable.” (2)

Relationships between artists and engineers evolved significantly with the Pavilion. Whereas, in 9 Evenings, artists related primarily to engineers, with the Pavilion project their main concern was with corporate rather than engineering culture. This shift is perhaps best introduced in Klüver’s press statement, entitled “Background,” which was released jointly by E.A.T. and Pepsi-Cola on September 30, 1969. It begins as follows: “E.A.T. is interested in Pepsi-Cola, not art. Our organization tried to interest, seduce and involve industry into participating in the process of making art.” (1)

According to Calvin Tomkins, E.A.T. became involved in the Osaka Pavilion Project through Klüver, who had been contacted by Robert Breer. Breer, the first artist to become involved, heard about the project from David Thomas, Vice President for Marketing and Distribution with Pepsi-Cola International. Prior to his involvement in 9 Evenings, Breer had been ‘leery’ of the artist-engineer collaboration, although he found the open-ended approach employed by Klüver exciting. When Breer suggested to David Thomas that the Pepsi Company bring in E.A.T. to coordinate the project, it was because he felt that, through E.A.T., artists could cope with the commercial establishment without getting broken. E.A.T. could act as a buffer behind which they could operate more freely and more effectively in their own style. Robert Whitman, who was drawn into the Pepsi project, shared Breer's conviction. “With E.A.T.,” he said, “artists have for the first time had access to professionals on their own level in other worlds. This is a funny thing. Any artist, whether or not he had anything to do wit E.A.T., has professional status and is suddenly more respectable.” (2)

Frances Dyson © 2006 FDL

(1) The Pepsi-Cola Pavilion / Experiments in Art and Technology; PepsiCo International ([September 1969], press release), [4] p. The Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science, and Technology, Collection of Documents Published by Experiments in Art and Technology. EAT C7-9 / 4; 136.

(2) Calvin Tomkins, “Outside Art,” Pavilion, edited by Billy Klüver, Julie Martin and Barbara Rose (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972), p.8

Index:

- Enduring Rhetorics

• Artists's Tangle

• Sound's Pre-Mix

• Three Phases of Rhetoric

• Billy Klüver - 9 Evenings

• Emerging Aesthetics

• John Cage

• Alex Hay

• David Tudor - The Pavilion

• Why the Pavilion?

• Sound

• Environment and Cybernetics - Art and Technology

• Artist meets Engineer

• E.A.T. meets Pepsi

• Automation meets Arts