Please wait a few moments while we process your request

Hervé Fischer

Images du futur past

[Editor's note: Mr. Hervé Fischer, founder with Ginette Major of Images du futur, 1986-1996, was commissioned to write this text.]

Even the future inevitably grows old. And barring some final catastrophe, it ends up in an archive. Still it feels odd to talk about the archives of Images du futur (the annual exhibition Ginette Major and I first mounted in 1985, back in the last century!) as an exploration of the unknown.

Let’s hope we will age well. For that, people must see real value in the vivid documentation on art and new technologies that we amassed over 12 years. In planning our programming each year, Ginette and I visited enough artist studios in Russia, Japan, Europe, Australia, Latin America and China that we managed to meet nearly every pioneer artist in electronic and digital art. Today, we can confidently say that the documentation we kept so assiduously (correspondence, installation diagrams, theoretical texts, catalogues, books, photos, slides and videos) is truly representative of the eighties and nineties, the two decades in which this new trend in art first blossomed. It was an age of adventure that was sometimes uncertain but always passionate.

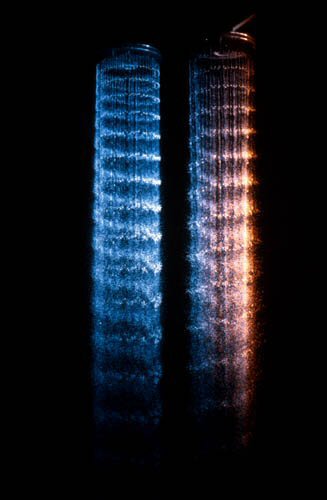

True, the four- to five-month-long exhibitions held each summer in the venerable passenger terminal (the one-time dock for passenger ships in Montreal’s Old Port) are no more. The exhibitions required budgets that snowballed as more sophisticated technologies appeared on the scene. But over the years, Images du futur put more than a million visitors in contact with the most daring multimedia creations of the time. Each year, we showed work by about 30 installation artists–over 400 artists in all. We celebrated an annual theme: artists from Japan (1987 and 1994), California (1992), New York City (1993), Germany (1991), France (1986 and 1989), as well as holography (1990), virtual realities (1995) and the cyberworld (1996).

From 1987 to 1996, we also organized a parallel event, the Images du futur international computer animation competition. The exhibition’s movie theatre offered audiences a selection of the year’s production in computer animation. People’s choice awards and international jury prizes were bestowed on the best creations of the year during a ceremony held at Place des Arts, the Théâtre Saint-Denis or the Imperial Cinema in Montreal. Thanks to the competition, we amassed a major international video library of computer-animated productions–the only one in Canada. This library helps tell the story, along with the Images du futur archives, of the pioneer era of digital art. Without wanting to diminish the importance of today’s creative work, I’ll risk saying that we lived through the most heroic and fascinating times in the development of digital art–the early years.

Let me start from the beginning. Our first challenge was to talk the management of Montreal’s Old Port into renting us the abandoned passenger terminal where scant years before, boatloads of travellers and immigrants had been arriving. Once that was accomplished, we had a huge 3,000-square-metre space, with customs halls and garage doors, that had to be totally refurbished and darkened.

Our first office had last served as a rental outlet for cross-country ski boots, since the unused spaces in the Old Port attracted winter skiers in those days. Our first archives, today carefully stored and organized by the Daniel Langlois Foundation, were stacked along the boot racks. Well, it was practical! The Old Port eventually renovated its decrepit warehouses and built an Imax theatre and a science centre. Our first office became an information kiosk and then public washrooms before finally falling to the wrecking ball. Today, our old passenger terminal is a parking lot, and it costs more to enter the lot than it did to see Images du futur. We can’t feel sorry for ourselves, though, because after all we were the pioneers of the future past

We always worked under very trying conditions. Each year, we had to start from zero, passing the hat to government ministries, city hall and our sponsors and begging for support, all the while hoping the public would come in droves (ticket sales were two-thirds of our budget). It was nerve-racking because we never managed to secure even a minimal ongoing budget. One time, Canada Council officials reported that they’d seen spiders in a corner and that this violated grant requirements. And I bet there were spiders given how close we were to the water. On top of that, rain would drip onto the exhibition at some point every summer because the roof was in such bad shape. We learned to live with these drawbacks. We hope everyone has forgiven us. Nam June Paik and Tsai forgave us, as did many lesser-known artists who depended on Images du futur since few museums were willing to show their work in those days.

In the eighties, most official art critics held the view that digital art, interactive multimedia installations, computer-cinema and holography were simply gadgets and even a Faustian compromise with big business. At best, they were bread and circuses for the general public. Critics refused to see the works as real art and either ignored or tossed barbs at us. Thankfully, the TV networks didn’t snub us but helped us reach a large audience that loved Images du futur and kept us going for 11 years. That era has gone, and today electronic art is what’s hot, while painting is less lauded. Yet I haven’t forgotten the battles in the eighties to have digital art recognized, battles I ended up championing in spite of myself.

We forged unforgettable friendships and loyalties with the artists. Without their understanding and support for this shared journey, there would have been no Images du futur. Indeed, we were at the forefront in understanding the methods the artists adopted and the difficulties–aesthetic, technical, institutional and financial–they faced.

At the same time, we watched individual styles and cultural differences emerge. In the first years of Images du futur, there were few differences between the works of American, Japanese and French artists. The artists made use of computer tools and software rather systematically because, although fascinated by new technologies, they weren’t yet agile enough to play up all the possibilities for expression. Dream Flight or Tony de Peltrie, a short computer-animated piece shown in 1996 in which a pianist’s dream unfolds, was the first attempt at creating a screenplay for an electronic cinema that was not yet born. Finally, it was born in Quebec, and Images du futur spread the news internationally.

As time went on, cultural differences made themselves felt. It was possible to distinguish the 3-D virtuosity of American creators pushing a powerful new technology to the maximum, the more sombre colours and dramatic expressions of German artists, French creativity in areas like 2-D, the sophistication of futurist detail in Japanese work, and so on.

In 1989, to demonstrate that computers could help in explaining references to the past and contain serious, even critical content (in those days, critics were still haranguing us about the superficiality of digital art and its compromises with big business), we decided to dedicate Images du futur to the bicentennial anniversary of the French Revolution. We chose artists from several countries and assigned each a production budget. The experience and exhibition proved costly but passionate. We made our point, though admittedly attendance dropped given the public’s lack of interest in history. We had to plead for understanding from the bank to survive that year!

To pull together all these exhibitions and organize the computer animation competition, we created a non-profit entity, Cité des arts et des nouvelles technologies de Montréal. Under this banner, we also staged exhibitions of art and new technologies abroad, as close as Rochester in the United States and as far as Munich and Weimar, Germany, and Lisbon, Portugal.

With so many projects on the go, we hoped eventually to get a continuing budget from the Canadian and Quebec governments and a building where we could offer a regular program of events, exhibitions and encounters for the new digital culture. But despite 12 years of successful activity, this never happened. It’s unfortunately not an uncommon story.

Still, the adventure called Images du futur has its place in history. What I recall, above all, is participating with some 400 artists in investigating electronic aesthetics, the public’s relationship with these new art forms, the evolving ideology of the art object, and the difficulties in preserving the new works. Yes, digital arts radically challenge the fine arts system. We must think of these works in light of an aesthetic of time, eventfulness and multimedia. Yet we still lack the concepts and analytical systems to do so. What’s clear is that these works are no longer unique objects to be signed, preserved and put on the art market. If artist survival can’t depend on collectors any longer, then new forms of financing must be found for digital arts, perhaps closer to those used for music, theatre or dance, such as commissions. Art galleries have shown little interest in this art form and don’t advertise it in art magazines. As a result, the magazines themselves give little space to digital art.

Digital art also poses an enormous challenge to museums. In a few years, the computers and software used by artists to make the works won’t be readily available. Indeed, in 10 or 20 years, it will be impossible to maintain outdated computers and keep them running. All that will be left of this "art of the future" will be documentation. What a paradox: the works will vanish even though they were created with the most sophisticated technologies. That’s why it’s crucial that the Daniel Langlois Foundation preserve and house our archives and make them available to researchers. Digital artworks have become as ephemeral as African masks eaten by termites. Handprints in prehistoric caves, as the Langlois Foundation logo testifies, have been with us for centuries, whereas works of digital art last only a few years or even hours. Art and progress don’t mix, it seems, from either a technological or spiritual standpoint. (I was trying to touch on this in my own paintings of handprints done in the seventies, before I was lured by the arts of the digital age.) But is this ephemeral nature a reason to depreciate digital art? Of course not. Life itself is fleeting, and thus even more precious. Indeed, in digital art, I’ve discovered the essence of art’s meaning, which, in the final analysis, is both iconic and archaic.

Even the future inevitably grows old. And barring some final catastrophe, it ends up in an archive. Still it feels odd to talk about the archives of Images du futur (the annual exhibition Ginette Major and I first mounted in 1985, back in the last century!) as an exploration of the unknown.

Let’s hope we will age well. For that, people must see real value in the vivid documentation on art and new technologies that we amassed over 12 years. In planning our programming each year, Ginette and I visited enough artist studios in Russia, Japan, Europe, Australia, Latin America and China that we managed to meet nearly every pioneer artist in electronic and digital art. Today, we can confidently say that the documentation we kept so assiduously (correspondence, installation diagrams, theoretical texts, catalogues, books, photos, slides and videos) is truly representative of the eighties and nineties, the two decades in which this new trend in art first blossomed. It was an age of adventure that was sometimes uncertain but always passionate.

True, the four- to five-month-long exhibitions held each summer in the venerable passenger terminal (the one-time dock for passenger ships in Montreal’s Old Port) are no more. The exhibitions required budgets that snowballed as more sophisticated technologies appeared on the scene. But over the years, Images du futur put more than a million visitors in contact with the most daring multimedia creations of the time. Each year, we showed work by about 30 installation artists–over 400 artists in all. We celebrated an annual theme: artists from Japan (1987 and 1994), California (1992), New York City (1993), Germany (1991), France (1986 and 1989), as well as holography (1990), virtual realities (1995) and the cyberworld (1996).

From 1987 to 1996, we also organized a parallel event, the Images du futur international computer animation competition. The exhibition’s movie theatre offered audiences a selection of the year’s production in computer animation. People’s choice awards and international jury prizes were bestowed on the best creations of the year during a ceremony held at Place des Arts, the Théâtre Saint-Denis or the Imperial Cinema in Montreal. Thanks to the competition, we amassed a major international video library of computer-animated productions–the only one in Canada. This library helps tell the story, along with the Images du futur archives, of the pioneer era of digital art. Without wanting to diminish the importance of today’s creative work, I’ll risk saying that we lived through the most heroic and fascinating times in the development of digital art–the early years.

Let me start from the beginning. Our first challenge was to talk the management of Montreal’s Old Port into renting us the abandoned passenger terminal where scant years before, boatloads of travellers and immigrants had been arriving. Once that was accomplished, we had a huge 3,000-square-metre space, with customs halls and garage doors, that had to be totally refurbished and darkened.

Our first office had last served as a rental outlet for cross-country ski boots, since the unused spaces in the Old Port attracted winter skiers in those days. Our first archives, today carefully stored and organized by the Daniel Langlois Foundation, were stacked along the boot racks. Well, it was practical! The Old Port eventually renovated its decrepit warehouses and built an Imax theatre and a science centre. Our first office became an information kiosk and then public washrooms before finally falling to the wrecking ball. Today, our old passenger terminal is a parking lot, and it costs more to enter the lot than it did to see Images du futur. We can’t feel sorry for ourselves, though, because after all we were the pioneers of the future past

We always worked under very trying conditions. Each year, we had to start from zero, passing the hat to government ministries, city hall and our sponsors and begging for support, all the while hoping the public would come in droves (ticket sales were two-thirds of our budget). It was nerve-racking because we never managed to secure even a minimal ongoing budget. One time, Canada Council officials reported that they’d seen spiders in a corner and that this violated grant requirements. And I bet there were spiders given how close we were to the water. On top of that, rain would drip onto the exhibition at some point every summer because the roof was in such bad shape. We learned to live with these drawbacks. We hope everyone has forgiven us. Nam June Paik and Tsai forgave us, as did many lesser-known artists who depended on Images du futur since few museums were willing to show their work in those days.

In the eighties, most official art critics held the view that digital art, interactive multimedia installations, computer-cinema and holography were simply gadgets and even a Faustian compromise with big business. At best, they were bread and circuses for the general public. Critics refused to see the works as real art and either ignored or tossed barbs at us. Thankfully, the TV networks didn’t snub us but helped us reach a large audience that loved Images du futur and kept us going for 11 years. That era has gone, and today electronic art is what’s hot, while painting is less lauded. Yet I haven’t forgotten the battles in the eighties to have digital art recognized, battles I ended up championing in spite of myself.

We forged unforgettable friendships and loyalties with the artists. Without their understanding and support for this shared journey, there would have been no Images du futur. Indeed, we were at the forefront in understanding the methods the artists adopted and the difficulties–aesthetic, technical, institutional and financial–they faced.

At the same time, we watched individual styles and cultural differences emerge. In the first years of Images du futur, there were few differences between the works of American, Japanese and French artists. The artists made use of computer tools and software rather systematically because, although fascinated by new technologies, they weren’t yet agile enough to play up all the possibilities for expression. Dream Flight or Tony de Peltrie, a short computer-animated piece shown in 1996 in which a pianist’s dream unfolds, was the first attempt at creating a screenplay for an electronic cinema that was not yet born. Finally, it was born in Quebec, and Images du futur spread the news internationally.

As time went on, cultural differences made themselves felt. It was possible to distinguish the 3-D virtuosity of American creators pushing a powerful new technology to the maximum, the more sombre colours and dramatic expressions of German artists, French creativity in areas like 2-D, the sophistication of futurist detail in Japanese work, and so on.

In 1989, to demonstrate that computers could help in explaining references to the past and contain serious, even critical content (in those days, critics were still haranguing us about the superficiality of digital art and its compromises with big business), we decided to dedicate Images du futur to the bicentennial anniversary of the French Revolution. We chose artists from several countries and assigned each a production budget. The experience and exhibition proved costly but passionate. We made our point, though admittedly attendance dropped given the public’s lack of interest in history. We had to plead for understanding from the bank to survive that year!

To pull together all these exhibitions and organize the computer animation competition, we created a non-profit entity, Cité des arts et des nouvelles technologies de Montréal. Under this banner, we also staged exhibitions of art and new technologies abroad, as close as Rochester in the United States and as far as Munich and Weimar, Germany, and Lisbon, Portugal.

With so many projects on the go, we hoped eventually to get a continuing budget from the Canadian and Quebec governments and a building where we could offer a regular program of events, exhibitions and encounters for the new digital culture. But despite 12 years of successful activity, this never happened. It’s unfortunately not an uncommon story.

Still, the adventure called Images du futur has its place in history. What I recall, above all, is participating with some 400 artists in investigating electronic aesthetics, the public’s relationship with these new art forms, the evolving ideology of the art object, and the difficulties in preserving the new works. Yes, digital arts radically challenge the fine arts system. We must think of these works in light of an aesthetic of time, eventfulness and multimedia. Yet we still lack the concepts and analytical systems to do so. What’s clear is that these works are no longer unique objects to be signed, preserved and put on the art market. If artist survival can’t depend on collectors any longer, then new forms of financing must be found for digital arts, perhaps closer to those used for music, theatre or dance, such as commissions. Art galleries have shown little interest in this art form and don’t advertise it in art magazines. As a result, the magazines themselves give little space to digital art.

Digital art also poses an enormous challenge to museums. In a few years, the computers and software used by artists to make the works won’t be readily available. Indeed, in 10 or 20 years, it will be impossible to maintain outdated computers and keep them running. All that will be left of this "art of the future" will be documentation. What a paradox: the works will vanish even though they were created with the most sophisticated technologies. That’s why it’s crucial that the Daniel Langlois Foundation preserve and house our archives and make them available to researchers. Digital artworks have become as ephemeral as African masks eaten by termites. Handprints in prehistoric caves, as the Langlois Foundation logo testifies, have been with us for centuries, whereas works of digital art last only a few years or even hours. Art and progress don’t mix, it seems, from either a technological or spiritual standpoint. (I was trying to touch on this in my own paintings of handprints done in the seventies, before I was lured by the arts of the digital age.) But is this ephemeral nature a reason to depreciate digital art? Of course not. Life itself is fleeting, and thus even more precious. Indeed, in digital art, I’ve discovered the essence of art’s meaning, which, in the final analysis, is both iconic and archaic.

Hervé Fischer © 2000 FDL

Related pages:

Hervé Fischer

Hervé FischerHe is co-founder and co-president with Ginette Major, of La Cité des arts et des nouvelles technologies de Montréal.

Images du Futur collection

Images du Futur collectionThis collection, which runs from the eighties to the mid-nineties, brings together international documentation corresponding to the 10-year history of the Images du Futur event.