David Rokeby

(Toronto, Ontario, Canada)

Rokeby's best-known series of installations, Very Nervous System (1986 to present), was first displayed at the Venice Biennale in 1986 and has since been consistently shown around the world. His work has been exhibited in shows across Canada, the United States, Europe, Japan and Korea, including SIGGRAPH'88 Art Show (Atlanta, U.S., 1988), Ars Electronica (Linz, Austria, 1991), Mediale (Hamburg, Germany, 1993), the Power Plant (Toronto, Canada, 1995), the Kwangju Biennale (Kwangju, Korea, 1995), Holly Solomon Gallery (New York City, U.S., 1996) and the Biennale di Firenze (Florence, Italy, 1996). Rokeby won the first Petro-Canada Award for Media Arts in 1988 and the Prix Ars Electronica Award of Distinction for Interactive Art (Austria) in 1991, 1997 with Paul Garrin and again in 2002. (2) This same year, Rokeby won the Governor's General Visual and Media Arts Award.

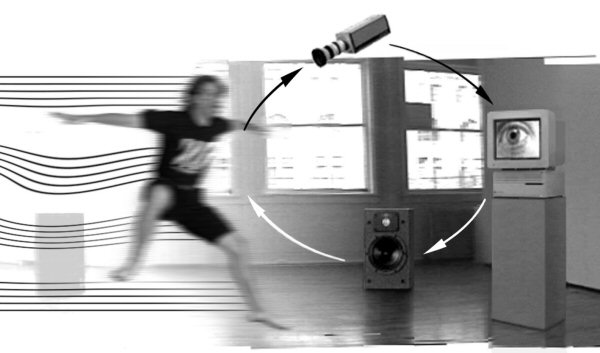

David Rokeby's first major interactive work was exhibited in 1984 at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, Canada. Body Language (1984-1986) was a cybernetic sculpture made up of three computers, a synthesizer, three video cameras, a digitally controlled mixer and an amplification system designed to transform what the camera saw into a complex sound environment and video images. Visitors were invited to dance or make dynamic or minimal movements with their body while the computer program designed by Rokeby read these movements and translated them into music. One of Rokeby's main concerns in this piece was the issue of interactivity. He wanted to explore how visitors could implicate themselves in the piece without controlling their movements or predicting the results of their gestures. The body's relationship to movement has been a major preoccupation for Rokeby, and he spoke of this in an early interview in Musicworks.

"People find out more about their resistance to movement in public than they do about their body. They still don't think enough about their body, in general. They think more about feeling comfortable or uncomfortable in the space. But at a certain point they might become seduced enough by the experience so they aren't thinking about that anymore, and then they're surprised at what they just finished doing." (3)

Rokeby considers Body Language the precursor to Very Nervous System, (1986 to present), his most widely known series of installations. Movement translated into music or images is the basis for the work, which evolved out of Rokeby's early interest in interactive systems.

Very Nervous System has been presented primarily in galleries, though it also has been installed in public outdoor spaces and used in several performances. Rokeby notes that:

"I created the work for many reasons, but perhaps the most pervasive reason was a simple impulse towards contrariness. The computer as a medium is strongly biased. And so my impulse while using the computer was to work solidly against these biases. Because the computer is purely logical, the language of interaction should strive to be intuitive. Because the computer removes you from your body, the body should be strongly engaged. Because the computer's activity takes place on the tiny playing fields of integrated circuits, the encounter with the computer should take place in human-scaled physical space. Because the computer is objective and disinterested, the experience should be intimate." (4)

Very Nervous System is also the name of the interface designed by Rokeby to capture movement and translate it into sound or music. The system has been used not only by Rokeby; many artists, programmers and researchers have acquired a copy of the software for their own installations or artistic projects. As well, Rokeby's system has been adopted by medical researchers and even a woman with cerebral palsy. The system translates the woman's eye movements into words to enable her to communicate efficiently.

Subsequent installations designed by Rokeby in the eighties include Echoing Narcissus (1987) and Liquid Language (1989). The former consists of a voice processor that plays back sounds in a cycle and is placed in the bottom of a barrel resembling a copper drinking fountain. At the bottom of the barrel is a sheet of Mylar that ripples and reflects visitors' faces. Rokeby's intention is to examine "the ways that technology modifies, enhances and distorts our image of ourselves." (5)

In the early nineties, Rokeby began working on another complex series of installations but this time making them subtler and less performative for the visitors. (Perception Is) The Master of Space (1990), Measure (1992-94), Petite Terre (avec Erik Samakh) (1992), Silicon Remembers Carbon (1993-2000), 60 (1995) and Watch (1995) are examples of the works created during this time. Using surveillance equipment, motion captors and custom-designed computer programs, these works all explore interactivity and what Rokeby calls "functional content." In an informative article in the catalogue for the exhibition Touch/Touché (first presented at the Mackenzie Art Gallery in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada), Rokeby writes:

"The resulting sensations of the relationship between audience and artwork, intention and result, real and virtual are what I would call the 'functional' content of the work, as differentiated from the images, sound, narrative, and whatever else might be considered as the content of the work in the traditional sense of the word." (6)

This preoccupation with the relationship between visitor and artwork permeates all his interactive pieces in a sensitive rather than invasive manner. For Rokeby, the challenge is to design a system that counters contemporary interactive works that remain predictable and controllable.

More recently, Rokeby has been working on a project first begun in the eighties. The Giver of Names was shown in its initial version (The Giver of Names: The Wanderer) for the first time in 1997 at Interaccess Gallery in Toronto, Canada. A second version, simply called The Giver of Names, was presented in 1998 at Oboro in Montreal, Canada. This project uses the loop of Very Nervous System but becomes a slower responding installation. Instead of processing movement instantaneously, the system studies objects selected by the visitor, processes information about the object (such as colour, shape and size) and then speaks a sentence aloud that describes its impressions of the object. Responses given by the computer are directly linked to a relational database in which Rokeby has programmed many words and associations. Visitors can read the processes of association on a computer screen incorporated into the installation. The mechanics and rational "behaviour" of the computer are therefore laid bare. Visitors are encouraged to recognize the non-human, non-emotional qualities of the computer process, although the metaphorical statements presented to them about their chosen object are infused with personal meaning in a completely subjective manner. Ernestine Daubner notes:

"Does it not, in fact, make visible or evident a process that occurs in the interpretation of all artworks? Is the viewer, in effect, not always really an interactor? Is the viewer not always inextricably linked to, and part of the meaning of a work of art? Is the notion of an a priori meaning by an intentional artist not simply an illusion? Rokeby's Giver of Names makes explicit what many artworks obscure: that one always encounters an art object (any object for that matter) as a mediated subject. There can, therefore, be no universal viewing experience; there can be no recognition of an a priori meaning." (7)

In January 2001, Presentation House Gallery (8) (North Vancouver, Canada) exhibited the recent versions of some of his most well known works including the Giver of Names (1998) and Watch (1995).

More recently, while continuing to exhibit and develop Very Nervous System and The Giver of Names, Rokeby has created several new installations including Border Patrol (1998) with Paul Garrin, Universal Translator (1999), Watched and Measured (2000), Shock Absorber (2001), Guardian Angel (2001) and n-Cha(n)t (2001) shown in 2001 at the Walter Phillips Gallery (9) (Banff, Alberta, Canada). Based on the software used in The Giver of Names, n-Cha(n)t essentially recycles the same techniques for generating linguistic units. In this work, a network of computers operating in unison shares a stream of semantic associations.

Angela Plohman © 2002 FDL

(1) http://homepage.mac.com/davidrokeby/home.html

(2) http://media.macm.org/biobiblio/garrin_p/2garrin-biblio.htm

(3) David Rokeby, "Cybernetic Installation : First Real Snake" Musicworks no 33 (Winter 1985-1986): 7.

(4) David Rokeby: Very Nervous System, (accessed August 7, 2000): http://homepage.mac.com/davidrokeby/vns.html

(5) David Rokeby, quoted in Christopher Hume, [unknown title], The Toronto Star (june 19, 1987) : n.p.

(6) David Rokeby, "Where the Virtual Meets the Real" in Touch/Touché (Regina : Mackenzie Art Gallery, 1999): 12.

(7) Ernestine Daubner, Interactive Strategies and Dialogical Allegories : Encountering David Rokeby's Transforming Mirrors Through Marcel Duchamp's Open Windows and Closed Doors, (accessed August 5, 2000): http://homepage.mac.com/davidrokeby/daubner.html

Related pages:

David Rokeby, Common sense gathering and discursive structure for The Giver of Names project

David Rokeby, Common sense gathering and discursive structure for The Giver of Names projectThe Giver of Names explores complex phenomena in the linguistic systems of both man and machine.

David Rokeby, Machine for Taking Time, (Boul. Saint-Laurent), 2007

David Rokeby, Machine for Taking Time, (Boul. Saint-Laurent), 2007In the fall of 2005, the Daniel Langlois Foundation asked Rokeby to create a version of Machine for Taking Time for the Ex-Centris building in Montreal.

Caroline Langill, Shifting Polarities, Interview with David Rokeby

Caroline Langill, Shifting Polarities, Interview with David RokebyBorn in Tillsonburg (Ontario) in 1960, David Rokeby studied at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto under Norman White, graduating in experimental arts.

The Giver of Names: Documentary Collection, Interview with David Rokeby

The Giver of Names: Documentary Collection, Interview with David RokebyThis interview with David Rokeby took place on September 18th, 2007 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and was conducted by Lizzie Muller and Caitlin Jones and filmed by Paul Kuranko.

Presentation House Gallery, Exhibition of Works by David Rokeby

Presentation House Gallery, Exhibition of Works by David RokebyIn 2000, the Foundation partially funded an exhibition of works by Canadian artist David Rokeby at Presentation House Gallery, a public visual art facility in North Vancouver.

David Rokeby, Very Nervous System (1983-)

David Rokeby, Very Nervous System (1983-)Very Nervous System celebrity and longevity pose some particularly interesting questions about documentation and contextualisation of media artworks over time and through change.

External link:

http://www.davidrokeby.com/