Please wait a few moments while we process your request

Caroline Langill, Shifting Polarities

Interaction and immersion

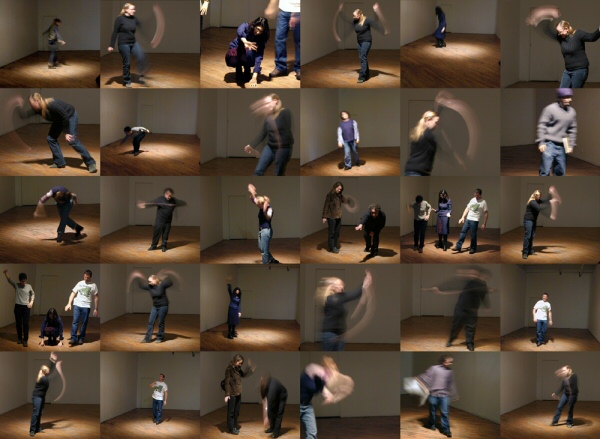

In contrast, David Rokeby’s Very Nervous System (1986-1990) offers no visible technology for the viewer. In fact there is no object: the object has dissolved. The audience members perform the work as their bodies create sounds that alert them to the work’s presence. Very Nervous System is Rokeby’s signature work. Like Jean-Pierre Boyer’s Boyetizeur, it is an artwork, an invention, and a tool of production.

The network between the audience and the work in Very Nervous System is again present in Diana Burgoyne’s Hanging One from 1989. The artist-machine-audience triad Burgoyne constructs in Hanging One is reminiscent of Jana Sterbak’s Remote Control (1989) in terms of the creation of a distributed social network. Remote Control and Hanging One signal an abandonment of material agents in favour of technological systems that are distributed between the body of the audience and the body of the work, and in the case of Burgoyne, the body of the artist.

Distributed systems suggest the potential for immersive environments. Alan Dunning’s Translation (1991) is an open work that takes its point of departure from the translation work done by the artist’s mother. Reproducing a stain found on a page of one of his mother’s translations to a disproportionate size, the author created a work foundational within his œuvre for the way it points back to his experience with early Xerox technologies and forward to his experiments with virtual reality in The Einstein’s Brain Project (1995-2001).

The questions preoccupying Dunning as he shifted from physically immersive works that consumed the gallery to virtually immersive works were similar to those postulated by Catherine Richards and Nell Tenhaaf when they collaborated on the Bioapparatus seminar held at the Banff Centre for the Arts in 1991. This event brought together artists from across Canada to consider questions of technology, biology, and embodiment. Nell Tenhaaf’s interest in tracking the genomic narrative of the new biology within a critique of scientific objectivity was evident in her work Species Life (1989). Richards also undertook a critique of science in Spectral Bodies (1991), an exploration of simulation and subjectivity. Together, Richards and Tenhaaf created a rich dialogue inviting artists to consider similar questions regarding their role within scientific debates of technology. The document that resulted from the symposium is one of the most valuable books available on artists’ perceptions of technological engagement in Canada. Now out of print and rare in libraries, the Bioapparatus document is a significant text that needs to be recognized for the contribution it made to the discourse of new media art at a time when artists and scholars were struggling to articulate this new genre of art practice.

Distributed systems suggest the potential for immersive environments. Alan Dunning’s Translation (1991) is an open work that takes its point of departure from the translation work done by the artist’s mother. Reproducing a stain found on a page of one of his mother’s translations to a disproportionate size, the author created a work foundational within his œuvre for the way it points back to his experience with early Xerox technologies and forward to his experiments with virtual reality in The Einstein’s Brain Project (1995-2001).

The questions preoccupying Dunning as he shifted from physically immersive works that consumed the gallery to virtually immersive works were similar to those postulated by Catherine Richards and Nell Tenhaaf when they collaborated on the Bioapparatus seminar held at the Banff Centre for the Arts in 1991. This event brought together artists from across Canada to consider questions of technology, biology, and embodiment. Nell Tenhaaf’s interest in tracking the genomic narrative of the new biology within a critique of scientific objectivity was evident in her work Species Life (1989). Richards also undertook a critique of science in Spectral Bodies (1991), an exploration of simulation and subjectivity. Together, Richards and Tenhaaf created a rich dialogue inviting artists to consider similar questions regarding their role within scientific debates of technology. The document that resulted from the symposium is one of the most valuable books available on artists’ perceptions of technological engagement in Canada. Now out of print and rare in libraries, the Bioapparatus document is a significant text that needs to be recognized for the contribution it made to the discourse of new media art at a time when artists and scholars were struggling to articulate this new genre of art practice.

Caroline Langill © 2009 FDL

Index:

- Caroline Langill, Shifting Polarities

• Introduction

• Early electronic media works

• Electronic media in 1974

• Between science and art

• Machinic aesthetics

• Interaction and immersion

• Conclusion

• Bibliography

• Selected works - Artist bios and interviews

• Doug Back

• Mowry Baden

• Jean-Pierre Boyer

• Roland Brener

• Diana Burgoyne

• Max Dean

• Alan Dunning

• Murray Favro

• Vera Frenkel

• Juan Geuer

• Laura Kikauka

• Gordon Monahan

• Nancy Paterson

• Catherine Richards

• David Rokeby

• Michael Snow

• Tom Sherman

• Jana Sterbak

• Nell Tenhaaf

• Norman White